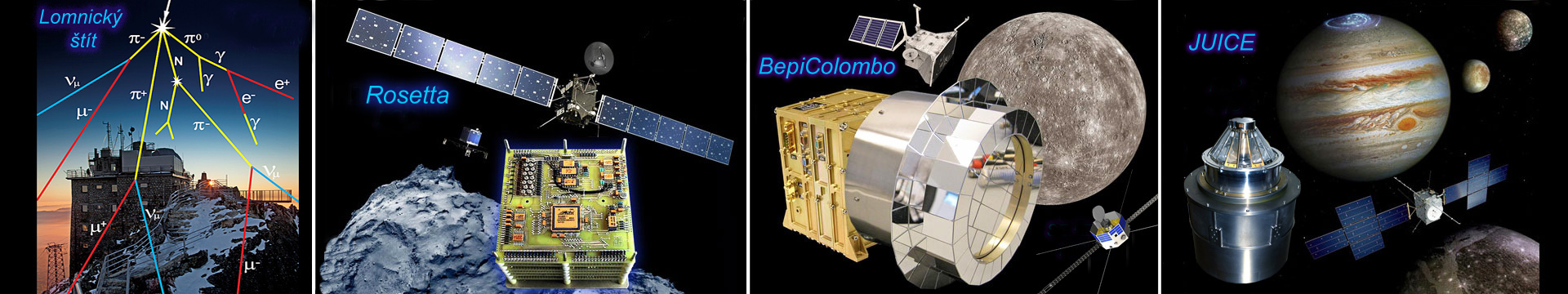

ESA’s BepiColombo probe successfully on a “halfway” to Mercury

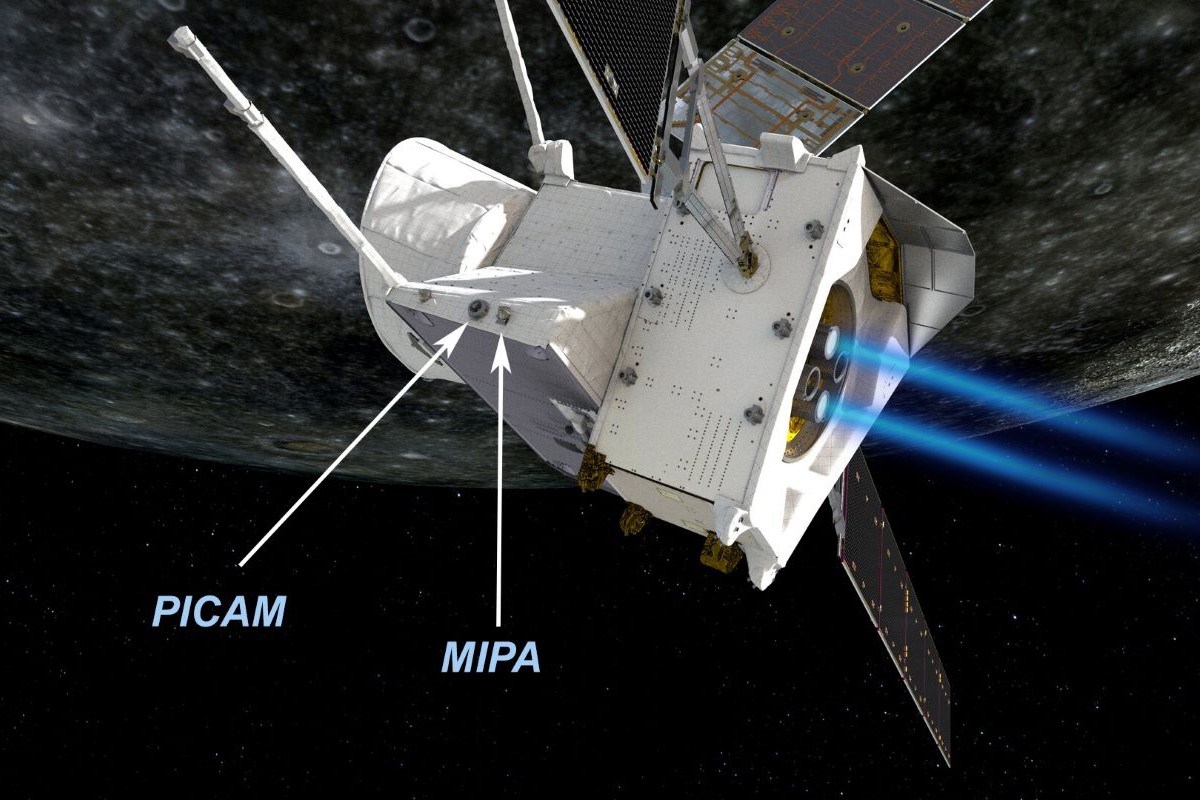

The BepiColombo interplanetary probe was launched by ESA towards Mercury in October 2018, and the main research tasks await it in December 2025, when it will “park” in orbit around this planet. The halfway point to Mercury is only a matter of time, but not of distance, because the probe is already approaching the planet and its scientific equipment is producing the first unique results.

The main problem, why the probe have not yet parked near Mercury, is related to the laws of celestial mechanics and limited energy resources for interplanetary flights. Since the probe started from the Earth’s orbit, which is further from the Sun than the orbit of Mercury, it is accelerated by the Sun’s gravity on the way to this planet, so it basically “falls” towards the Sun, and if it was not continuously braked, it would gain too high a speed. Despite being braked by chemical and unique ion engines and assisted by gravity on close flybys of Earth, Venus and Mercury itself, the probe is still flying past it too fast to be gravitationally locked into its orbit. So far, the probe has used one gravitational assist from Earth, two from Venus and two from Mercury itself, from which it will need four more. The Italian scientist Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo, in whose honor the probe is named, made the calculations according to which the probe is currently optimally flying to Mercury using gravity assistance.

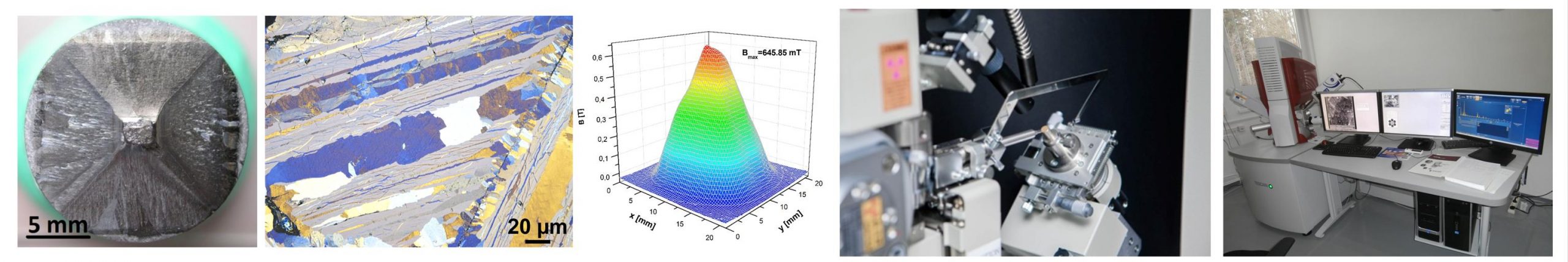

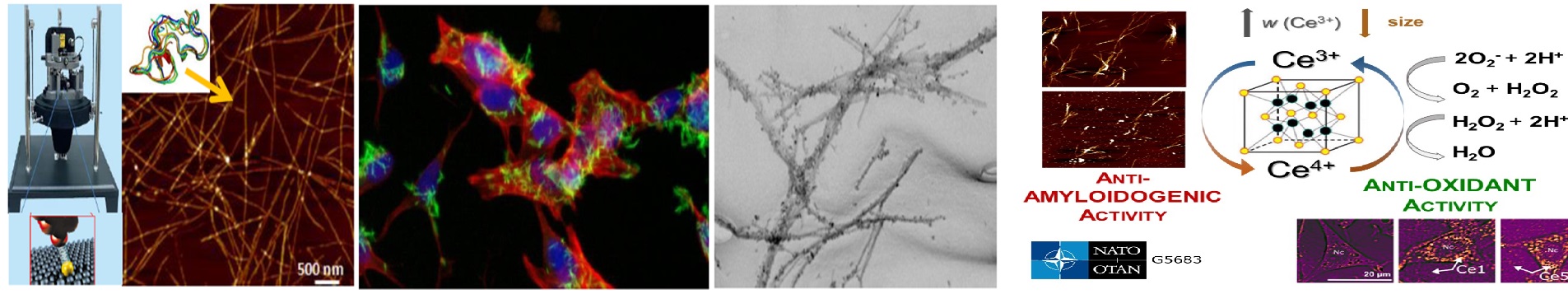

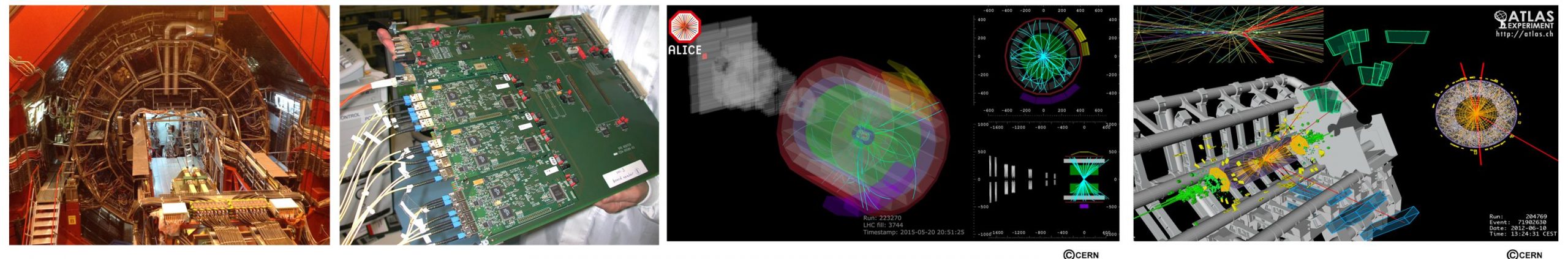

The BepiColombo probe, worth more than two billion euros, consists of three parts: the European MPO planetary orbiter, the Japanese MMO (Mio) magnetospheric orbiter, and the MTM transfer module, which provides propulsion and maneuvers with chemical and ion engines. However, not all scientific equipment can work actively now, as the sensors of some are blocked by the transfer module. Among the “lucky ones” with a free field of view is the ion mass spectrometer PICAM (Planetary Ion CAMera). “PICAM was constructed as part of a very broad international collaboration with the contribution of our Institute of Experimental Physics SAS and Slovak technology companies,” stated one of its designers, Ing. Ján Baláž, PhD. The sensors PICAM and MIPA (Miniature Ion Precipitation Analyser) are part of the scientific complex SERENA (Search for Exospheric Refilling and Emitted Natural Abundances) and recorded unique scientific data in its southern inner magnetosphere during its first flyby of Mercury. These data have been published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Communications, and are affiliate to the Institute of Experimental Physics SAS as well.

Original source

Original text and photo: Department of Space Physics

Contact

Contact Intranet

Intranet SK

SK